Drugs & Alcohol, Guest Posts, Newsletter Articles, Posts for Parents, Raising Adolescents

The top 5 issues facing teens today: a doctor’s perspective

A note from Maggie: In researching my forthcoming book, Help Me Help My Teen, I have heard from a range of clinicians and experts who work with adolescents. One such clinician was GP Dr Andrew Leech, who was kind enough to allow me to share a post from him, with his observations about the adolescents he sees in his practice every day. Please note this post does include talk about some very difficult issues, such as eating disorders, self-harm and suicide. Please seek help from one of the many support services that exist, should you need it.

A guest post from Dr Andrew Leech

FRACGP, MBBS, B.Sci, DipChildHealth

It has been a significant time of learning and upskilling for General Practitioners (GPs) working in primary care as we encompass this new ‘gen-alpha’ and all the amazing, creative, exciting possibilities they bring with them. We sit at the forefront of the ups and downs our young people experience and are often the first point of call when they need someone other than their parents, caregivers, teachers, or friends.

All teenagers need a good GP—someone they can trust and talk to. They need a safe space to explore some of the key health and mental health issues that keep coming up in their lives.

It is a privilege to be a sounding board and it is not uncommon for them to say things like –

‘Mum and Dad might not understand’.

‘My friends will think I’m weird’.

They feel isolated, trapped almost in those troubling thoughts and feelings.

From the challenges I see, teens are just trying to fit in and be accepted by their peers, families, and even themselves. The path to acceptance can either be easy and straightforward or rocky and risky. Parents need to understand that they can’t control that path. They can guide and suggest things, role model and give examples, and be open to conversation without judgment, but the ultimate path a teenager takes in life is their own. This is developmentally normal. We have become all too fearful of the unknowns out there and over-protective of our children. We need to learn to let them go and experience the world, to spread their wings and to build resilience by making mistakes.

GPs also need to take the time to upskill and be aware of current issues facing young people. We can’t be ignorant of the fact that times are different. We are not their parent and shouldn’t judge. So many teens tell me about doctors who have told them off, just like their parents did, for smoking weed or having sex when we should be chatting openly, supporting and educating them with these decisions. Teenagers have not yet developed the capacity to make informed decisions or judgments in the face of peer pressure or complicated situations. They often get caught in a cycle and can’t find the way out. Some turn to self-harm, even suicide.

Youth suicide is the number one cause of death in 18–25-year olds. This is a tragedy. We need to keep working on prevention collaboratively. Through our healthcare system, parenting support programs, schools and education systems. The implementation of the ‘HEADDSS screening tool’ for General Practice around 15 years ago was part of this solution. An easy to remember acronym that prompted us to consider the important parts of a teen’s life, home, education, alcohol and drugs, sexuality, spirituality and suicidal ideations.

In my consultations with teenage patients, these are the top five issues they’re facing right now.

1. Social media & gaming

Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok. The three apps they all talk about.

Whether we like it or not, these apps shape a big part of a young person’s communication with others. Whether they are ‘DMing’ their friends or group chats with kids at school, these apps are front and centre of a young person’s world. We sometimes even joke when I catch them checking a message mid-conversation with me. I notice the glance down at their chair, and they always look surprised when I say, ‘Who messaged you?!’

This is a huge part of a teen’s perception of themselves, identifying that they might not be as pretty, skinny, or outgoing as the other teens they see on Instagram. Young people are easily influenced by what they see in media in all forms.

The risk varies so greatly. Some can see others for who they are without comparing themselves. Others I see feel inadequate and worthless by simply scrolling and seeing others’ posts online. Then there are those who don’t mind too much about seeing the current trends but also can’t help but try to be part of those trends.

Those most vulnerable to social media cannot filter out all that noise and they can become completely absorbed. They might convince themselves to starve, skip meals at school (by throwing them in the bin because their parents won’t know the difference), secretly start weighing themselves and not giving in until they reach that ‘set weight’. Anorexia is so severe and so challenging to treat and often goes unnoticed until much later when they can no longer hide under baggy jumpers. Binge eating disorder is more prevalent but equally challenging for teens. The emotional toll taken on them can be so strong that they find comfort in food.

Dealing with social media in primary care has been more about understanding the teen’s purpose and meaning, and less about providing clear guidelines.

I have seen teenagers who have had their phones confiscated by parents for poor behaviour. This can have a significant impact on them. The person they most trusted, their parent, who gave them that phone, has now taken it away as a punishment. There are two issues to highlight. One is that they now feel they have no one. At that moment, after making a mistake which they will most likely regret and feel ashamed about later; they have been disconnected from friends through their communication portals and family due to the anger and frustration in the house. As hard as it is to believe, the consequence of this can be extreme.

I’ve seen it and cannot emphasise enough that teenagers will make mistakes in their lives and need to learn how to deal with their choices, but we need to be able to work with them and educate them on better ways forward. Our parents are also learning. Taking away a phone as a sudden punishment is like taking away food for some teenagers. It is a significant part of their life. [Note from Maggie: Check out Brad Marshall’s book How to say no to your phone for some tips for parents and teens on managing this].

Whether we like it or not, social media, phones and online communication are here to stay. Our support for young people in healthily navigating this is to teach them appropriate boundaries that enable them to engage in activities without a screen. Anything involving movement, face-to-face social connection with family or friends, good sleep and rest, and time to read or use their creative skills will be essential to using a screen.

Gaming addiction can be equally problematic. Online gaming forms an escape for increasing numbers of teenagers and is an important part of their relaxation time. However, those who cannot switch off a device after a set time do often end up with difficulties in their mental health. The cascade of this can be easily seen. Less time outside, less sleep, less social contact, less interest, or motivation to go to school. Suddenly, that online world becomes their reality.

Some suggested strategies for managing social media.

- Teens and their parents need to work together and not against each other.

It might be a message that confuses them, a person asking them to do something they’re uncomfortable with, or arguing about something they feel strongly about. If my teen patients are ever uncomfortable in a conversation, app, game, or on any device, they need to reach out and speak to that trusting person for the next best step. - Agree on some good boundaries and setting reminders to stop using the phone.

I often suggest to my teen patients that they set up ‘do not disturb’ mode on their phone.

Our brains are programmed to read every message until the inbox is empty. Night mode turns those little numbers off and any other incoming irrelevant messages. I advise them: Do not disturb ‘your time’—space and time to yourself where you feel happiest. Have a routine that helps you wind down for sleep without screens. This can include reading, listening to music, mindfulness, sketching or colouring, or even chatting with your parents in the living room. - Nothing is so wrong that you can’t figure it out.

It can be figured out no matter what happens online and inside their social worlds. One teen I saw who shared a nude selfie certainly didn’t feel that way. He received his punishment, including a school suspension and confiscation of his phone. But my message to him was that life will go on, and tomorrow, there will be something else people will discuss. Your nude selfie is not that interesting anymore. You will get through this. - Gaming addiction therapy.

Some states, such as here in WA, offer a gaming addiction outpatient service. [KidsHelpLine has some good resources to refer to as well.]

More from Maggie: Take a listen to our Parental As Anything episodes on Kids and Gaming . Also there’s an episode on Teaching Kids Body Positivity. You may also find Maggie’s article on 10 Agreements for Healthy Balance helpful for excessive gaming or social media use among your teens.

2. Drugs and Alcohol

Almost every week, I’m still finding out what the ‘coolest’ drug is out there!

I still have to stop sometimes and ask ‘what exactly is that?’ Drugs like nangs, lean (codeine + lemonade), weed / devil’s lettuce / Mary-J / coosh (marijuana), MDMA, coke (cocaine), Es / pills (ecstasy), dexies (dexamphetamine), vaping, shrooms / mushies (mushrooms) or for the lazy option you could just text

Rikkodeine is still easily accessible over the counter in Australia despite repeated warnings that children can die from overdose.

Alcohol remains the most significant risk to young people, being the most accessible and easiest to hide drug, but significantly damaging to young brains. Approximately ¾ of my teenage patients between the age of 13 and 17 would have consumed alcohol.

Strategies for drugs and alcohol use.

- Honesty and an open communication strategy.

I’m very open and honest in my education around the health effects of drug and alcohol consumption. After rapport is built with a teen, I have a good chance of providing targeted education about what they might be doing. Quite often, our schools provide education in a general format. However, teens can quickly forget the longer-term harm because, in that moment of being offered something, it doesn’t matter. It’s the cool thing to do. It’s an escape. This depends on the young person and how mature or accepting they might be. - Normalising a situation can often get me on the same page as them.

‘I get it; at that moment, you made a snap decision and made a mistake. Let’s work on ways to say to friends that you like spending time with them, but you don’t want to be pressured into drinking or taking drugs.’ - Drugs are harmful and lead to long-term damage that cannot be reversed.

Health issues like infertility, depression, anxiety, and even psychosis or hallucinations can all come from using drugs. I encourage my patients if it is too much, to step away from that group of friends and move to positive people in your life and people who respect your decisions. - Consider the importance of mental health.

Are they using the drug to try and escape from a more profound pain or anxiety? Is there a healthier way to cope with that? Treatment may require psychological support, medication such as an anti-depressant (SSRI) or referral to an adolescent psychiatrist. Some of my teens have required admission to hospital. Whilst this is difficult at the time, it can act as a ‘reset’ when they’re stuck in a difficult cycle. Headspace offers psychological support for free with a referral under a mental health care plan (more on this later). The average wait time to see a psychologist at Headspace is around 8 weeks.

More from Maggie: take a listen to Maggie’s chat with Paul Dillon about vaping and also check out the class she did with him about Alcohol, Drugs, Parties and Teens.

3. Self-harm and suicidal thoughts

One of the most challenging and confronting areas of a young person’s thought patterns is wanting to hurt themselves. I’ve spent years trying to understand why someone would like to do this by asking them, having open conversations about what drives the impulse, and listening.

Many don’t know why they cut themselves. It just happens, and then it becomes a behaviour that helps them cope when the world around them is too much to handle. Some teenagers describe self-harm as a way of turning mental pain into physical pain. This might come from being isolated in their thoughts and not knowing where to go next. This commonly occurs in the middle of the night. They don’t want to wake their parents, are unable to sleep, and their thoughts get the better of them. They become overwhelmed and start thinking about everything that was ‘bad’ about the day, and that tomorrow will be worse. This is not attention-seeking behaviour. This is a scary thought pattern. Teens will use anything they can find at that moment: broken glass from a picture, a razor blade, a knife from the kitchen, their nails, a pencil or pen. It is the tipping point of everything circulating in their mind and needing to ‘let it out’. The pain of cutting is the release of pressure and anxiety. It is relieving. Some of my teens self-harm in other ways. Pulling out hair or eyebrows, banging their head on the wall, punching the wall, or using drugs and alcohol.

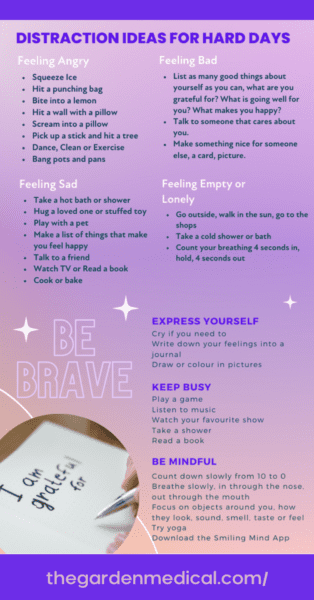

When talking to teens about harmful behaviours, I can never judge. Their impulse and lack of judgment at times of heightened distress causes an almost uncontrollable behaviour. It is essential to talk about it openly and create a list of practical ideas that can be used as an alternative. Teens need an open dialogue at home when it comes to self-harm. This coping mechanism cannot be punished. I do get it, though; parents must feel overwhelmed when they first notice scars, cuts or scratches on their child’s forearms or legs. If a teen suddenly starts wearing long sleeves, it might be worth keeping an eye on them as the first way they tend to hide the scars is with their clothing.

Suicidal thoughts can be linked to self-harm, or they can be separate. One way I assess this is, ‘Were you self-harming with an intent to end your life?’

A teen who is trying to die needs very careful, sensitive, structured support and a safety plan.

They require professional help and a team they can trust and work with. This is the same for the teenager who has suicidal thoughts. Many of my young patients express periods in their lives that they describe feeling ‘suicidal’. We need to establish here whether these are suicidal thoughts that come with a plan of how to do it, or suicidal thoughts like ‘I’d be better off dead’, or ‘I just want to escape’ or ‘I just don’t care anymore’.

Suicidal ideation (thoughts like these just mentioned) tells me that this person is feeling helpless, trapped in a difficult situation at home or school, and not knowing where to turn next. Leaving them with negative thought patterns and seeing the world clouded and grey. In this state of despair, they often withdraw, lose interest in things, feel the world is against them, and forget to look for the good stuff.

Strategies for self-harm and suicidal ideation.

- Apps: Calm Harm, an app that tracks the number of days they’ve remained safe and avoided hurting themselves and provides tips on other ways to release the mental pain.Beyond Now is a fantastic app that allows teens to create safety plans. Too often, we give teens what we think is best for them. A standard ‘safety plan’ that at the end says ‘call Lifeline’. Teens tell me Lifeline is ‘ok’ but can take an hour to answer their call. Sometimes, this is an hour too long. I prefer a teen to be empowered to take control of the situation and develop their coping strategies. Whilst this sounds idealistic and too good to be true, they can do it, and it works. They know what they are doing is unsafe and dangerous, but sometimes they don’t know the alternatives.

- One safe support person.

If a teen has just one person they can trust and talk to, then I am much more confident that they will be okay. So even when we don’t know exactly what we need to do to help them, knowing they are supported by someone gives me some reassurance. - A gratitude journal.

I ask all teenagers to write down three good things about their day. We know that doing this for eight weeks improves mood and reduces stress. - Youth drop-in centres.

One of the most common messages teens tell me is they are sick of explaining their story over and over to different people. Or that they don’t want to go to a hospital’s Emergency Department. I agree with this and believe we need many more youth drop-in centres that operate 24/7, with face-to-face support in a calming, youth-friendly environment. Head to Health centres are starting to open across WA with plans for expansion of funded centres for young people. These centres could save lives. - Find a good GP.

All young people need a good GP to explain things just once, and then, they need to have that person follow their journey and advocate for them alongside their parent or support person. I believe a human interaction is far more effective than a ‘bot’. With the rise of AI, we are expecting a significant jump in the use of ‘bots’ to deal with human-based problems like youth mental health. Whilst this could be better than nothing, it is that feeling of isolation that leads teens to these difficult moments. We all crave human contact and interaction; this is in our DNA. - Headspace has set up an online counselling service (e-headspace) that can provide free chat and phone support.

- Dedicated child and adolescent mental health phone services.

Each state has a dedicated child and adolescent crisis line for unwell teenagers. I provide this to all teens and parents as a fridge magnet [you can find a list here]. Localised support by a support worker is often an excellent way to de-escalate situations and avoid the need for hospital care, but when in doubt, if there is an immediate risk to a teenager, the most important thing is to get them to the safest place possible, and that might still be the local hospital emergency department.I also created a self-harm ‘coping card’ that I often give teens who come through my clinic:

More from Maggie: Take a listen to the Parental As Anything episodes on how to talk about suicide, and the one on what to do if your child is self-harming.

4. Bullying

Bullying is not a new problem and probably hasn’t changed in prevalence over the years. It is the method through which teens pick on each other that has changed, with bullying becoming a 24/7 problem thanks to messaging apps on phones.

I saw a 14-year-old recently whose life was turned upside down when they sent their friend an inappropriate ‘selfie’.

Within minutes, the selfie was shared among other friends and reached the school community. For this teenager, it was a moment in time they would never get back. That one image led to suspension, embarrassment, and mental health distress – before long, they were self-harming and in a state of depression.

I also recently saw an 11-year-old who was sent Facebook messages online telling them they were ‘fat’ and ‘ugly’. As would be the case with any 11-year-old, they took it to heart and starved themselves of food for several days, with no-one at home or school realisin. They became unwell and ended up collapsing, leading to a trip to the ED.

We can’t judge these kids. Social media is designed to draw them in and trap them in a cycle of feeds, often with themes of physical appearances or how cool someone is.

It’s also developmentally normal for teenagers to make decisions without realising the consequences. So, it’s easy to understand why we’re seeing increasingly poor mental health outcomes because of social media use and, in particular, online bullying.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 70% of children aged 12–13 in 2016 experienced at least one bullying-like behaviour. That was before COVID lockdowns and the rise of apps like TikTok, which now has 8.5 million monthly users in Australia.

According to recent Australian e-safety research, 50% of teenagers aged 14–17 reported experiencing negative behaviours online, while a concerning 30% reported being contacted by a stranger they did not know.

The digital space is increasingly encroaching on young people’s lives, so GPs are pivotal in asking teenagers about their online encounters.

Around half of the teenagers I see tell me information about their online behaviours that they would not have told their parents or family – behaviours that put them at risk of harm but also play a role in their mental health.

Online bullying is no different to bullying at school and quite often is committed by the same perpetrators. It just means that instead of going home and forgetting about it, the bullying continues into the night, affecting their sleep. When we see young people with poor mental health, including self-harm and suicidal thoughts, we must enquire about their social worlds both at school and online. From my experience, bullying is one of the most significant contributing factors for children and teenagers harming themselves or becoming severely anxious or depressed. It is also a huge risk factor for eating disorders and school refusal.

We have yet to learn about TikTok at medical school and what our teens are doing online. The quickest way to know about it is to ask the patients themselves. I generally ask, ‘What apps are you using? What do you do on those apps? Who are you talking to, and what are you talking about?’ Once I have rapport, I have no issues asking these questions, especially if we can maintain confidentiality and speak to them independently.

Some suggested strategies for supporting teens with bullying.

- Allow teens to speak to someone.

Preferably separate to the family or friend network (GP, school counsellor, psychologist) with assurance of confidentiality. - Manage the mental health impact.

For teens, bullying can be the biggest thing that has ever happened to them, and they feel like there is no escape. Remind them that while it hurts right now and feels impossible to change, it will change and improve. - Keep an open dialogue with what is happening.

Try to find a positive collaboration with the school leadership team such as the principal or year co-ordinator. Things tend to work out better for everyone if parents can manage their own distress around what might be happening to their child and remain calm in these discussions. For some teenagers, the bullying has gone too far, and they may need to change schools. - Encourage teenagers to walk away from those who are upsetting them and to build resilience by not letting words and actions get in the way of who they are and how they feel about themselves. They must speak up, inform their parents, speak to a psychologist, and tell the school. It is not okay for others to treat them this way.

More from Maggie: Check out the Parental As Anything episode on Cyberbullying

5. Anxiety

Anxiety across all age groups is the biggest issue we are dealing with right now in primary healthcare. We have evolved to a point where our nervous system is hardwired to be more reactive, faster, and more stimulated by our screens and work whilst being more vulnerable to this stress. As we evolve into a technological world, could it be possible that we are genetically programming teenagers to have a permanent level of background anxiety?

We are a product of our parents, and the teens I see who struggle with anxiety can also have anxious parents. I see it when I talk to them. It is easy to let our worries get in the way of everyday, calm thoughts. It is easy to catastrophise what is going on for us and forget about the present moment.

Young people don’t necessarily have the tools just yet to manage that. What may be a thought about a complicated friendship can become a feeling of being overwhelmed and not wanting to go to school. This is not to say anxiety is abnormal. The sense of fear is a helpful warning when we are under stress, and I tell teens this. But I also teach them to observe and address that warning sign with their support network. I ask all young people about anxiety. I am surprised if there is a time that they haven’t had it for an extended period.

Anxiety doesn’t necessarily look the same in teens as it does in adults.

Anxiety in young people can present as a behaviour rather than an emotion. Avoidance of that situation, yelling and screaming due to being overwhelmed, self-harming to escape, having a panic attack in the toilet cubicle at school, and even running away. I also see teens later in the journey of anxiety where it has become so escalated they don’t know how to regulate their feelings, and often the whole house describes ‘walking on eggshells’.

Strategies for anxiety:

- Teaching mindfulness

I start with simple box breathing exercises for any situation that leads to uncomfortable emotions (4 seconds in, 4 seconds hold, 4 seconds out, 4 seconds hold and so on). - Sleep hygiene

Setting up a routine for more refreshing sleep that includes phones off an hour before bed, a choice of calming activity, going to bed when tired and not before that, using sleep sounds, white noise or audiobooks. - Simple lifestyle changes.

More outdoor time in nature, more exercise, more social contact face-to-face rather than virtually. - Involving allied-health professionals.

This can be a psychologist or occupational therapist (with mental health training), social worker or youth worker, depending on what might be acceptable to the young person and family and what situation they are dealing with. For this to succeed, they need to be matched with someone they might feel comfortable with. GPs are usually pretty good at figuring out who is in their area. This is not as easy in rural areas, but plenty of great psychologists offer telehealth support. - Getting a Mental Health Care Plan

The purpose of this is to develop practical goals that will help with improving mental health.

In Australia, a Mental Health Care Plan allows Medicare funding support for up to 10 sessions with a psychologist, accredited OT, or social worker. Some parents worry that a mental health plan will affect a child’s ‘health record’ for future employment opportunities. My thoughts around this are any employer who discriminates against a child who sought help for a mental health issue is not going to be a worthy employer of your child.The Medicare record should be confidential and only viewable by the parents and teen (unless the teenager is over 18 and has their own Medicare card, in which case they are the only one that can see their Medicare history).I believe in proactive care to prevent worsening long-term illness. If it ever required a statement, a GP should provide one with the support that this evidence-based intervention led to the right help at that time and should be treated no differently than any other health intervention we use. - Online Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

For more brief intervention there are some great online CBT courses offered. One I frequently refer teens to is the ‘This Way Up’ Clinic.If referred by a GP this is free to access and keeps the GP informed of the progress.

Teenagers are our future and the next generation to take on our jobs, have families and create a cleaner, calmer, more peaceful world.

Investing time and energy into all aspects of a young person’s life is priceless in helping them reach their full potential.

All young people are inherently good; this can become lost in the noise from media, what we hear in the news, seeing it firsthand in our families and frustrations at the mistakes they make along with the pushback we can get from them. A teenager’s journey in current times is not the same as it was in generations gone by. They are experiencing the world around them as a very different place than what we have ever seen before.

All we can do is be there when they need us, listen when it matters, try not to judge, and show kindness.

Just like when they were younger kids, teens still value quality time with us, and need us to show them we love them. The difference is they also need time out and space. They need people to empower them to develop into wonderful, amazing human beings.

Image credit: ©️Elnur_/Deposit Photos

Dr Andrew Leech is an Australian GP with a special interest in child and adolescent mental health. He is the Director of The Garden Family Medical Clinic in WA and, in 2023, he was named WA GP of the Year by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Hear more from Andrew at thegardenmedical.com

Manage Membership

Manage Membership