Anger, Self-regulation & Tantrums, Building Family Relationships, Newsletter Articles, Posts for Parents

Tricky transitions – why they happen, what can help

One of the most significant shifts in understanding the human brain, especially the developing child’s brain is that the brain loves predictability.

From birth, experiences that are perceived through the sensory processing systems, create mini predictable pathways. When the brain has a sense of what is coming, like it does with a bath time or bedtime routine, it doesn’t have to work too hard to predict what is happening next.

The two states that the brain finds trickiest are total rigidity and total chaos.

Change of any kind that is not anticipated or expected, or has been experienced before, will trigger the limbic brain to experience anxiety or stress. This is exactly how the brain is supposed to work – constantly scanning for possibilities of threats to survival.

Transitions are a form of change which, even though they are often necessary, can be difficult for children and teens. Struggling with transitions is developmentally normal. Phew that’s so good to know.

Transitions: the struggle is real

Given the immature nature of the brain architecture of young children, we need to accept that they can struggle with transitions without us feeling there is something seriously wrong with them, or our parenting.

If I am deeply engaged in a fabulous crime book, and my good bloke tells me it’s time to help him in the garden, I will be very resistant to that transition! Even though I love gardening and we may have agreed to do some together, in that moment my brain is making lots of dopamine, which is a neurochemical of enjoyment and engagement and I would not want to stop experiencing that.

Infants and toddlers are very much in a mindful state where the only thing that really matters is the moment they are in. They are not wired to hurry, they have very little concept of time and they are developing their own autonomy and just want to do what they enjoy doing. Simple eh?

No wonder they can struggle with transitions at times. Dr Lisa Feldman Barrett in her book How Emotions Are Made explains that the brain needs to learn things over and over, which equals statistical learning, in order for it to make accurate predictions in the future.

As I’ve indicated, transitions can appear as an unexpected threat to survival for little ones, so by helping them learn how to navigate them means we can help them manage change not just as a toddler, but also as an adult later in life.

Some things that can help with transitions in childhood

Some of the things that definitely do not help our little ones to move from something they want to do to something else is being commanded or demanded to do so! No human likes to be told what to do, so one of the first things to keep in mind is how we request the transition. Calling out across the distance tends to be quite unsuccessful, especially for little boys who are often so overly focused on the task at hand they don’t seem to register that anyone is talking to them!

Keep the mantra in your mind as a parent, connect and then direct. If your child is busy playing an imaginary game, you might come close to them and observe their play, and even possibly join their play.

You could have an imaginary character make the suggestion that soon it will be time for dinner. Or if your child has been building a Duplo farm, for example, you might acknowledge the amount of effort they have put into building, or ask where the cow is going to go before you make the suggestion that soon it will be time for dinner.

Tone and timing are key

Another key thing that helps with connecting before directing, is how you make your request. If you give them a rushed request from an anxious space within yourself, there is more of a chance they will resist. If you use a term of endearment and a warm, calm tone, even some safe touch if they enjoy it, it really increases the chances of them making the transition soon.

Allowing time for a child to change from what they are currently doing is not only helpful it is respectful. So often, things get very rushed and hurried especially in the mornings, and this can register in a young child as anxiety because things feel out of control. If you want your children to come to the breakfast table by 7 o’clock, then 15 minutes before is a great time to sow those seeds of possibility that they may need to prepare to change what they are doing.

The same happens if you have a time you need to leave the playground, that you give them messages about the upcoming transition. It can be also really helpful that you have prepared them before you got to the playground, that you have a departure time already in your mind and that you will give them some warnings as that time comes closer.

The brain is already registering that there is a timeframe around the play opportunity and it will be able to predict, that there will be some warnings so the child is not surprised when it is time to leave. It is also okay to validate for them that it can be hard to leave the playground when you are having fun, and that you hope to be able to come back on the weekend and have a longer play.

It is totally okay to give them a reason why you need to leave at that time, especially if it is to pick another child up, or because you need to cook dinner or because you need to stop off and pick up some milk as you’ve run out. Children can respond better – sometimes – if they know that you have a valid reason for ruining the fun!

If you are also struggling with transitions from playgrounds or even trips to the beach, keep an eye out for when there is a change in children’s play. Sometimes they decide to stop playing on one piece of equipment or building a sandcastle, and as that is already a change process, it can be easier to bring forward the news of the transition, rather than doing it in the middle of an engaged fun play opportunity.

Minding expectations

Another thing that I have noticed that can make a transition challenging, is having the expectation that a child can move onto something else which the parent is choosing, without having completed the task at hand. In Mothering Our Boys I share the experience of boys who play with Lego before school who are encouraged or persuaded to tidy up and pack it all away, before they get in the car to go to school. Sometimes they protest very loudly and can just feel really ripped off.

To enable that transition to go smoother, I suggest that parents tell their children, that it is time for us to go to school and if you haven’t finished what you were building, you can finish it after school. They might be in the middle of a magnificent creation so it’s good not to quash creativity too.

Change of any kind, especially when unexpected, unwanted or full of too much uncertainty can trigger anxiety and stress.

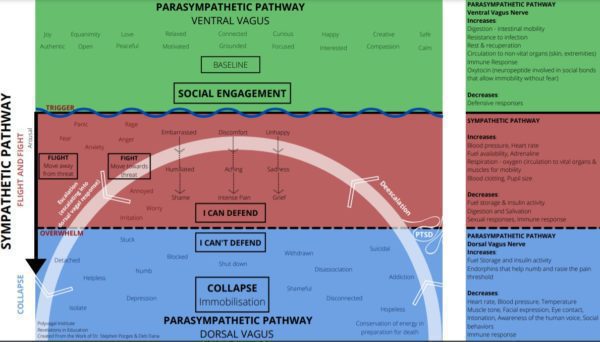

As Dr Mona Delahooke explains in her brilliant book Brain-Body Parenting, the body – via the vagus nerve – can trigger stress in a couple of different ways. The fight-flight pathway or the red zone is when children will kick, scream, throw things or hit others and it is important to remember that when this happens, your child is not being naughty your child is struggling to cope with their world and they are displaying distress.

The other pathway commonly called the freeze zone or blue zone is when children can appear quietly uncooperative, as though they are not listening, or sometimes withdraw from engaging with others – either socially or physically. If children are exhibiting these signs in your home, early childhood setting or school, they will find transitions of any kind particularly challenging.

Here’s a great image that illustrates that.

Image credit: Dr Lori Desautels/ Revelations in Education©2022.

Until they are able to feel safe and calm, transitions can quite simply overload the nervous systems and their behaviours will show this. This is the reason why punishing children whose behaviour can be challenging, does not help the child’s behaviour to improve. It merely causes more distress and possibly even more challenging behaviour.

As Dr Ross Greene says, “children will behave well if they can.” Helping children to have the skills to manage environments that they find difficult or stressful, and that includes around transitions, is the best way forward not only for the child but also for the educator or teacher. Having predictable classrooms, with warm safe grown-ups, in which children feel seen and heard makes such an enormous difference for children who struggle with a sensitive or hypervigilant nervous system.

Both Dr Delahooke and Dr Feldman Barrett stress the importance of co-regulation when our children are struggling because there has been a ‘prediction error’ with the world, which has created a moment of uncertainty, such as a transition from something they are happy to be doing.

Having a safe calm, grown-up is really important when our little ones are experiencing physiological distress. We can observe the storm, we can validate the storm however it is best not to join the storm! Sometimes this can be what happens when a child gets the wrong colour cup, or you have cut their toast the wrong way. The subsequent meltdown or tantrum is in response to an unconscious, automatic response in the child to a possible threat!

Maybe we should call a tantrum what it really is: a stress response to a prediction error!

In that very hot moment, they need to know that they have safe grown-ups who understand that they are not being naughty they are simply struggling to cope with the world. One simple way to help these prediction error moments with toddlers is to give them a choice of what colour cup they would like, or how they would like their toast cut BEFORE you do it!

The ‘body budget’

A child’s ability to cope with a prediction error, or an unexpected change or transition is also influenced by their body budget, as Dr Feldman Barrett calls it, which is quite simply how much energy is available in their whole being to help them cope in that moment.

If you can imagine a child who has had a poor night’s sleep, possibly with constipation, then their body budget for the day is already compromised and they will have less energy to manage the wrong colour cup or your flawed way of cutting up toast!

“Children often struggle with transitions because they have difficulty shifting gears. Some children find it stressful to shift to something new that is not self-directed. What we see as a result is a child with oppositional behaviours, whose body is managing the subsequent feelings and sensations around the cost of that shift.”

– Dr Mona Delahooke, Brain-Body Parenting (2022).

Parents who can attune to their children tend to navigate transition a little more effectively – although still not all the time. When our children have a face that says they are not in a positive space, we may handle a request for transition much more sensitively than we would if they were in a much happier frame of mind. There are times that it’s best to remember the mantra “don’t sweat the small stuff!”

Helping children with transitions when they are at preschool will be really helpful for when they transition in other ways throughout life. Transitioning to big school, high school, a new caravan site for holidays, a new home, or even the arrival of the new sibling –are all experiences full of uncertainty and the brain can become anxious because its ability to predict is impaired.

Realistic preparation for the upcoming change really matters. If we are overly positive about a transition, they can feel really ripped off. One of my sons was bitterly disappointed in the first week of big school because he hadn’t learn to read in five days and he couldn’t see any other point to going back!

Keep it light

The final tip to helping with transitions is to try doing it with novelty, lightness and laughter. If you suddenly turn into a dinosaur that wants to eat your child at the playground, as you encourage them to run to the safety of the car, it may work better than your endless nagging.

Singing and dancing can also be creative ways of helping with transitions because the positive neurochemicals of having fun can override the stress chemicals that have been triggered because a change has been forced upon you.

It can help to try a few different approaches to transitions while recognising that the limbic brain in our little ones is still growing in its ability to understand and cope with change and uncertainty. Our dandelion children, as Thomas W Boyd coined them, tend to cope with any of life’s little bumps and bruises better than our orchid children, and that is again not a sign of poor parenting, it is a sign of an increased sensitivity for our little ones.

The brain can learn to build pathways of certainty and predictability, with the help of safe calm grown-ups and lots of practice.

If there is one gift I have received from the pandemic, it is that I am so much better at unexpected change and uncertainty because I have experienced so much of it (we all have!).

Practice might not make one perfect, however it can improve future performance because the brain has had lots of predictability training. Put simply, this is exactly the same as what our children need no matter how frustrating it can be especially when we’re trying to get out the door in the morning – on time!

Image credit: ©️ By monkeybusiness / depositphotos.com

If you want to explore more on this, you might be interested in catching the replay of Maggie’s masterclass with Dr Mona Delahooke on Challenging Behaviour.

Manage Membership

Manage Membership